One thing that’s easy to carried away with, when you want to design your garden, is designing it bigger and better than it probably needs to be.

To ‘make it worth’ it. To impress neighbours, friends & family.

It’s a common trap people fall into, and it can quickly force you to spend more time maintaining something you don’t use, rather than enjoying it.

Just like getting a great car, but feeling it months later when you pay for insurance and servicing.

My tip?

Don’t design your garden for other people, just to impress them. You may find that many of the kinds of things you want to do ARE similar to others. But that doesn’t mean blindly copy activities, features, hobbies or other spaces because other people have them.

Even if they have them and suggest you have them too!

Don’t get a barbecue if you aren’t that interested in cleaning it, maintaining it or even cooking with it. Or a pool if you aren’t interested in swimming. And don’t get a shed or sandpit or cubby house or vegetable garden or other ‘thing’ if you aren’t into it.

So if you shouldn’t do any of those things, what should you do?

Design Your Garden By Choosing What YOU Want To Do & See

As you design your garden, and look at activities and features, think about what YOU want to do/see. Don’t put something in because it’s popular right now.

Things go in and out of fashion all the time, and falling for that can lead to a large expensive waste of space. Instead, think about things you want to leave the house for. These are the activities you want to focus on. Think about the things you want to see or experience. And that you’ll go to the effort of maintaining.

This maintaining point is important to consider. You’ll see below how you should consider it over a period of time. And not just when it is at an easy-to-manage level. What if it gets overgrown, or becomes a dormant space? How do you handle it at its worst?

It sounds obvious to design your garden around things you personally want to see and do. But as I mentioned above, it’s not always how people operate.

Go Down A Level –

How You Use The Space,

Can Shape The Space

So you need to put in the work to really understand what you want, and how you want, to design your garden. You can learn where to find landscaping ideas here, and how all this forms part of a larger landscape design process here.

Once you have your list of absolutely, 100%, must include activities, features or other garden ideas, we need to dig deeper for each one. Take the same thought process it took to get here, but apply it to a specific space.

To do this, take an activity or feature and think about how YOU will use it. Again, you don’t want to just paste in what you think is necessary. Think about your specific wants, needs, requirements etc. How YOU will use the space of your activity or feature.

As you design your garden, think about how much time and effort you’re willing to go to maintain a space. Don’t just put arbitrary sizes of things, or go big because you can. Really think about how you are likely to use it. I’ve got a trick to help you think about it, but first let’s look at an example or two.

Example – YOUR Raised Vegetable Beds

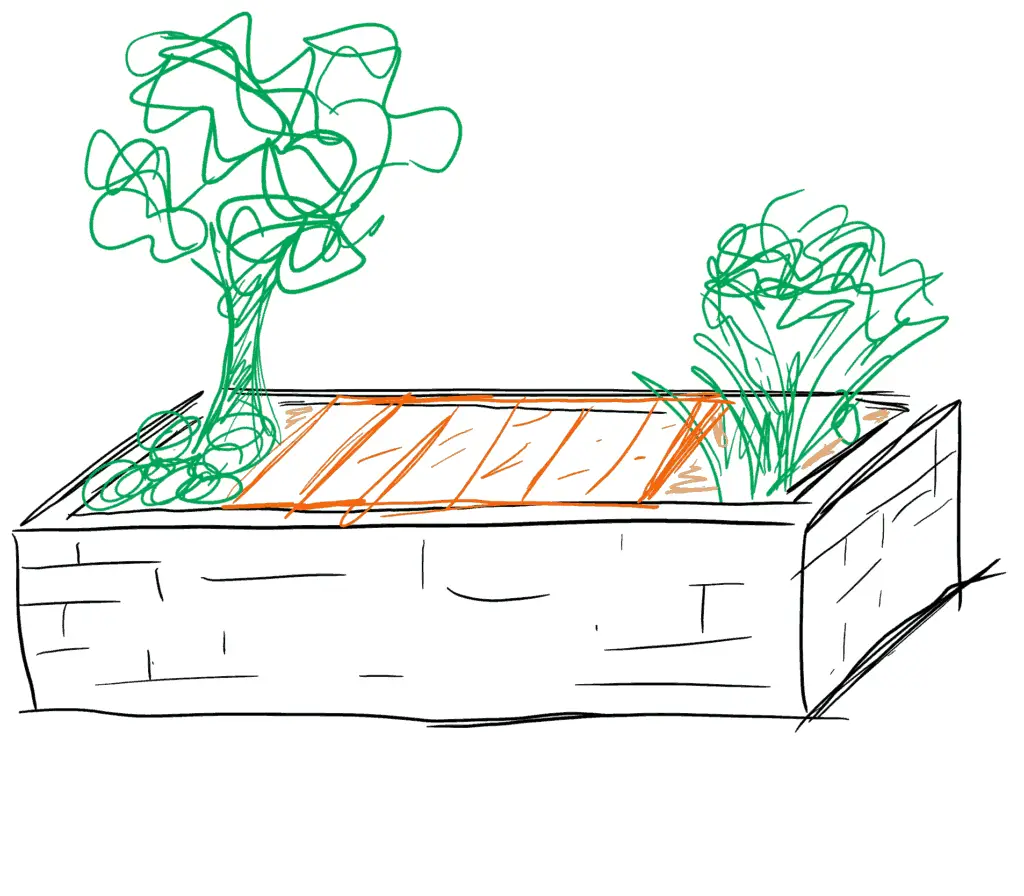

Imagine you want to include a set of raised vegetable garden beds in your garden design. Home gardening is definitely in right now. Raised beds are great because they’re easier to use – less bending and straining. They also make it easier to prepare the soil. And do basic maintenance. Also better for the elderly, or frail (or perhaps will-be-frail in the not-to-distant future).

Having a vegetable garden and growing your own produce is probably the right thing to do as well. Healthier food for your family. Less waste. More sustainable. It’s funny how historically we moved from self-sustainable growing a century ago, to a fascination with produced foods, back to a focus on self growing. But, I digress…

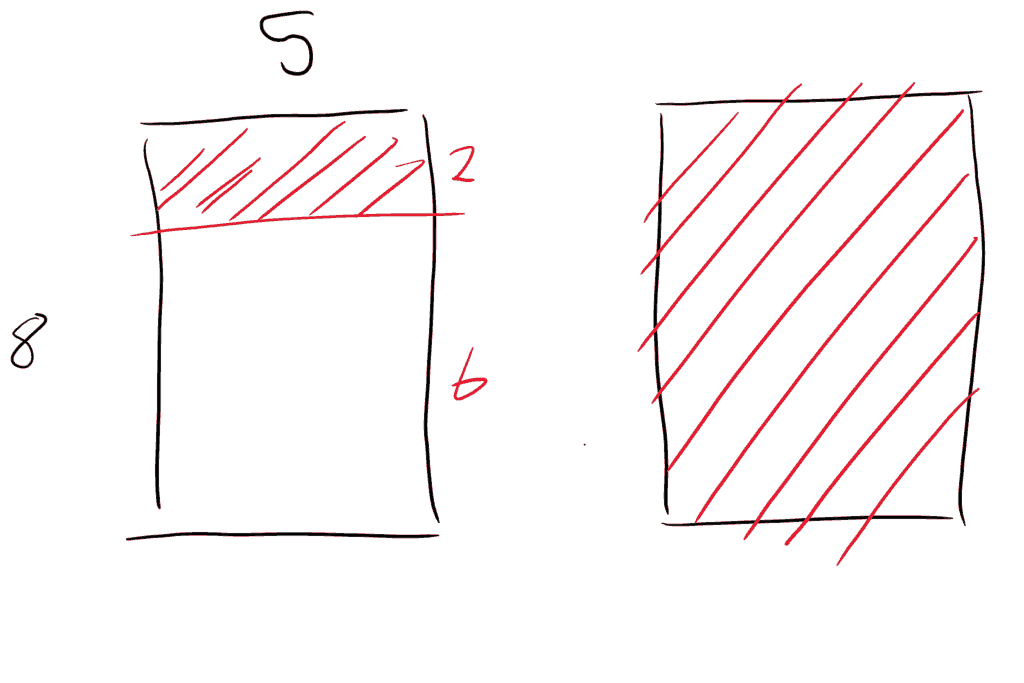

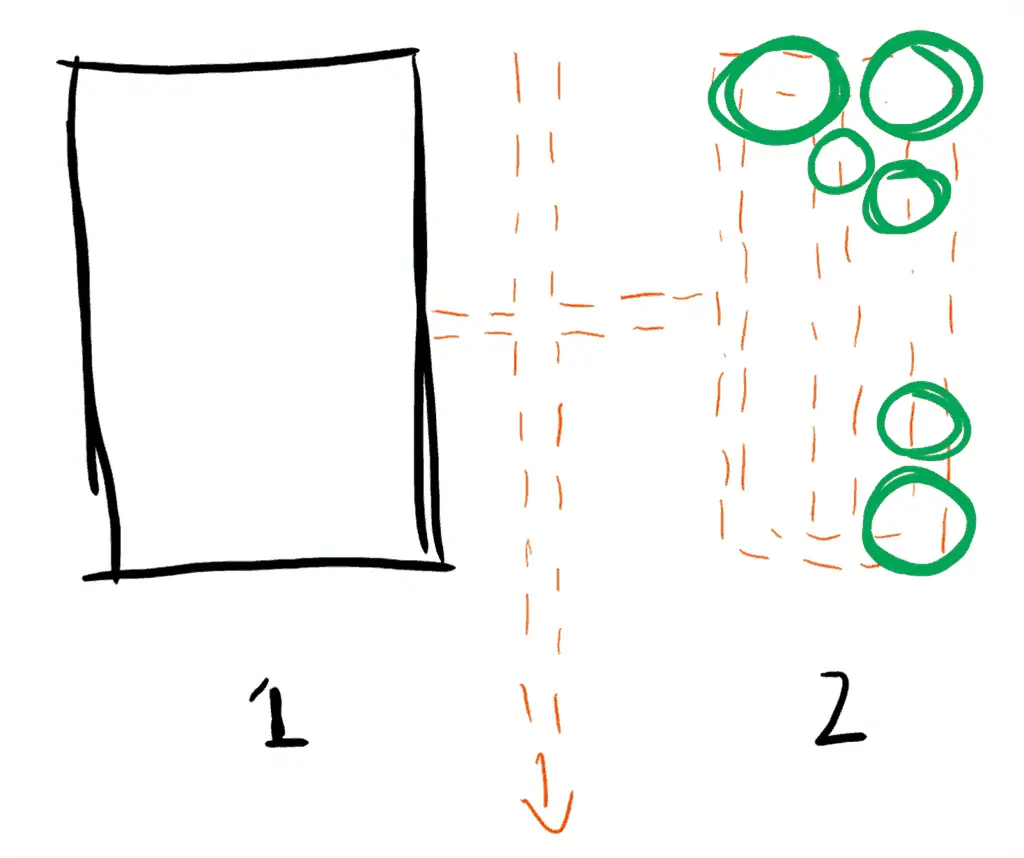

You want to see how you can design these raised beds in this position. You’ve got the space so you make two beds, 8ft long by 5 ft wide – because someone suggested it online. This 8 x 5 ft rectangle is a helpful ratio to follow to make things look nice.

Shows the ‘Golden Rectangle’ rule prescribed by Rob Steiner in his design principles article.

So, you have the beds in that position. They will look really nice, and you have plenty of space to grow tonnes of veggies. Once this is built and fleshed out, you’ll have an amazing vegetable garden, the envy of friends and neighbours. Something Pinterest or Insta-worthy.

Before you get all excited by the idea, consider – have you grown veggies before? Are you likely to follow through on the ‘promise’ you’ve made? To use that space to grow your own produce?

It’s a pretty big promise, as indicated by the space you’re attributing to this activity. Even if you have experience with herbs or veggies, how much are you actually likely to grow? Do you need multiple rows of the same thing? How likely is your family to eat all the things you grow?

There is no harm being aspirational. If that’s a goal for you, to grow more of your own food, that is a noble goal. But don’t go from a container of herbs to 80 square feet of growing space. Look into what other families of similar sizes grow. Do some research. Even better, if you have the chance, run a little experiment.

Option One – Test Run

Set up a smaller version of the activity – in this case a little garden bed or patch. This gives you an idea not only of how much size you might actually use, but also the requirements to keep the activity rolling.

How much time do you actually dedicate to it? To planting, soil prep, weeding, harvesting and all the other little things.

Option Two – Research & Calculate What You Use

If you don’t have the time or inclination to do a test run, let’s look at the other side of the equation – what does your family eat?

What do you cook? What do you want to cook? How much stuff do you need? If you can’t test how you’d use the space, quantify how much you think you need to effectively feed your family. What you may actually use.

Do you need that row of lettuce? Or will you use a few of them and the rest go to seed? Will you eat those potatoes you are attempting to grow? Will you use all the basil you plan on growing? Or just occasionally?

Do the research into your life and family situation now, before you put money towards over-engineering an activity you think you will like.

These options work wonders in helping you to think about an activity when you design your garden. Go beyond considering just the physical aspects. How much space you need between things. How high they should be. The materials you need. Consider what you’re likely to do with it. This thought process will help shape your spaces far better than just assuming. Or copying and pasting from an image.

There is a third option you can consider as you design your garden, or specific spaces. Think the worst…

Option Three – Consider The Worst Case Scenario

To appropriately size and scale your ideas/spaces as you design your garden, do the following:

Imagine it in the worst case scenario.

For our raised garden beds, this suggests something forlorn. Abandoned. Unkempt. Unused.

Depending on the position you’re testing, this may be something you could manage. Or, it could be an embarrassing display of a better, more hopeful time.

I want you to imagine yourself, in a few years perhaps, with this specific space.

Imagine you no longer spend the time on it that you used to. It could be for many reasons. It doesn’t matter why, what matters is the result.

In this case, the activity or feature is not as loved or cared for as it once was. The plants are either half dead, dying, or completely overgrown. The timber or stone or bricks are looking dirty and faded. It’s a little sad and lonely, which makes you sad and lonely every time you look at it.

Photo by Anne Heathen.

You imagined a future of overflowing, bountiful garden beds. Blossoming trees. Beautiful flowers and foliage.

But your present highlights your lack of time. You overestimated your free time, passion, inclination to maintain, and most likely the calm and control you thought your life would have. And now the results are sitting there, right there for all who visit to see.

Let’s look at the raised vegetable garden beds again. We are sticking with designing the 8×5 ft beds. Two of them. 80 square feet of growing space. We have plans on what we want to plant where. Aspirational goals to feed the family entirely from the vegetable garden.

Now imagine it with plants gone to seed. Strangly vegetation, or things not growing very well. Plants dying off because you didn’t remove them after their growing season is over.

Or perhaps even bare earth or soil. After one growing season, you got sick of the maintenance required, so it’s easiest to leave it bare.

This is not the scenario we want to be in. Luckily for you, imagination is not reality (unfortunately, some of the time). How do we build in some flexibility into this space? How can we design your garden to accommodate change? Not just the big ones (new pets, children – or less pets, children etc.), but the little ones. Changes to your availability. Or interest in caring for and maintaining the garden beds.

We can do this in a few different ways.

How To Design Your Garden To Handle Change

Handling change is mainly about having back up plans in place – contingency plans.

The first way to handle change is to do what you did above – think about how YOU will use the space – and design your garden appropriately.

Let’s have a quick look at the raised garden bed to see if they are appropriate:

Through calculating food intake, what meals I plan to cook, what I want to grow, how much I like or use my test run garden bed, I think the area I need is around 30 square feet. This covers all the space I can plant out and maintain for many years.

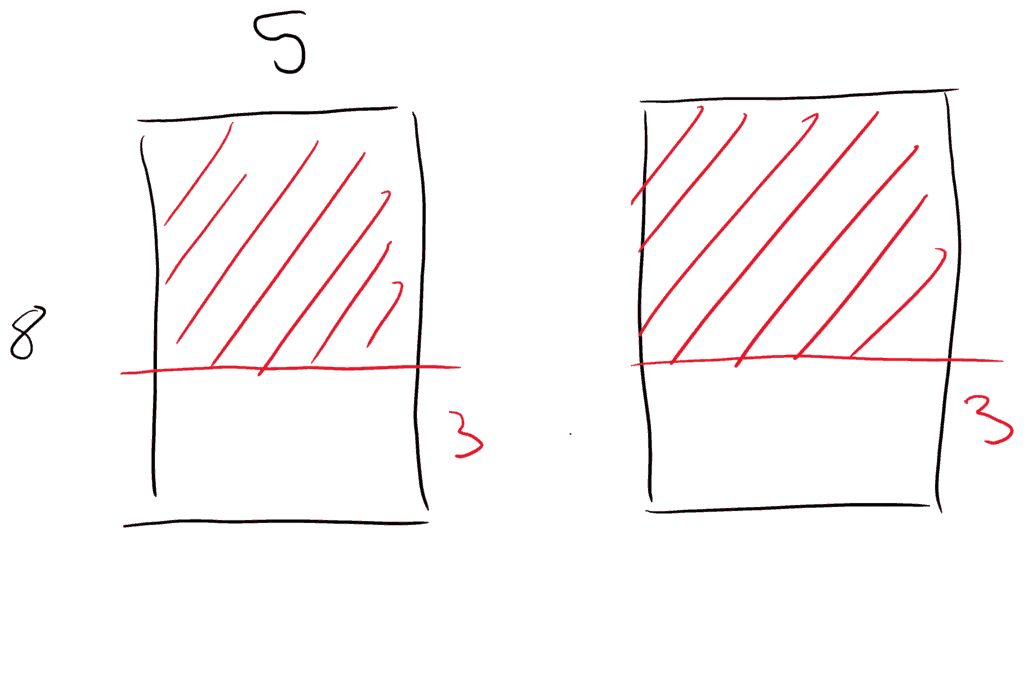

This means I can drastically reduce my garden beds in size from 80 square feet down to the suggested 30. I could do this by cutting down one garden bed.

Or reducing the size of both. These immediate physical changes would get me closer to something I can live with.

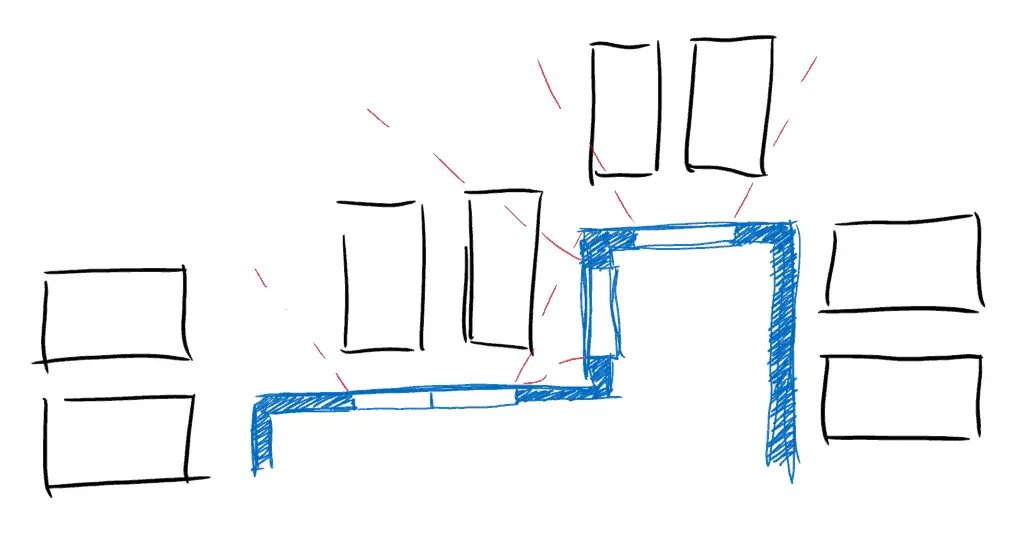

But, you may see this kind of change ruin your garden design completely. You think you need to keep the existing size and layout to make everything ‘work’. Let’s look at some contingency plans to put in place, if you find keeping 80 square feet of vegetable garden too much to handle.

Contingency Plans

Let’s keep the beds the same planned size. But, should I find that I don’t need all the space, or want to maintain beds that size, I have a few back up options. They could be:

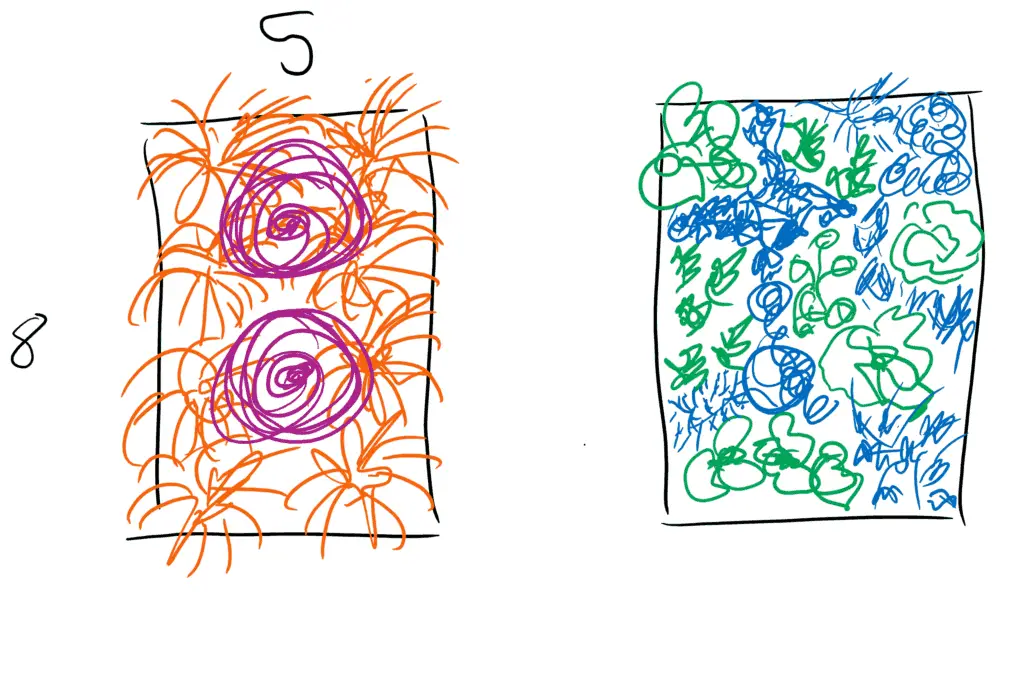

Have a plant option or two that are very low maintenance, and can be planted in bulk. Imagine planting a flowing mass of grasses that require a prune once a year. Or perhaps some smaller beautiful trees or plants that can be planted and left alone. Basically a set of back up plantings I can plant in one bed should I want to reduce the amount of vegetable garden space I have. In fact this idea could be spread across both – have a mix of inedible and edible plantings, make it much more ‘natural’ rather than clumping things together.

Or space out your edible plants – vegetables & herbs (green) – amongst some inedible plantings (blue).

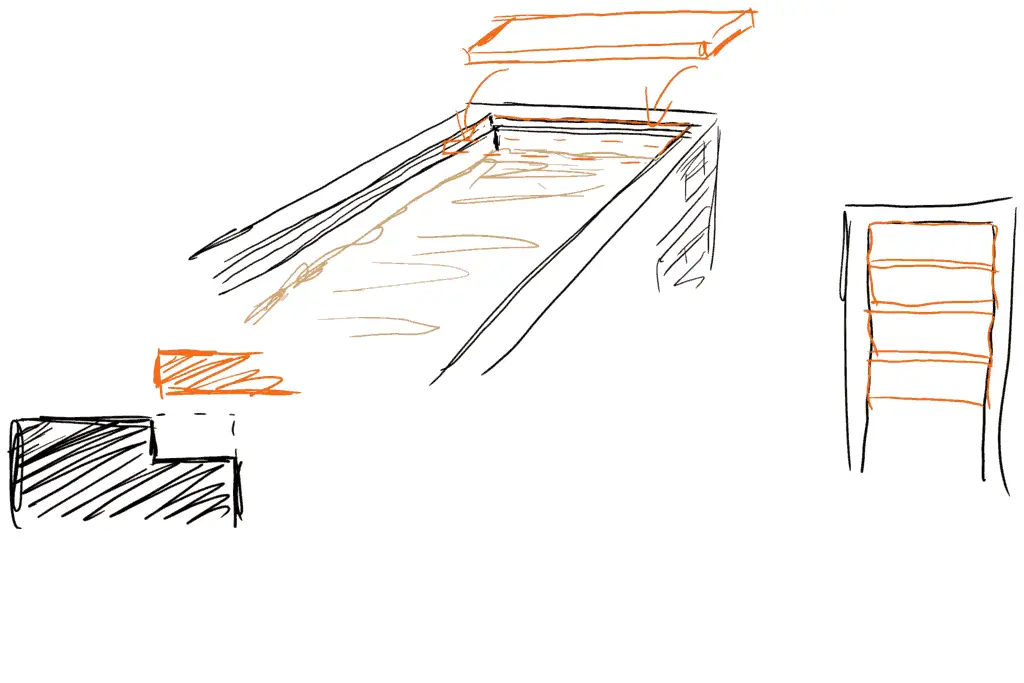

Style the raised beds in such a way as to allow them to be covered later on by another material. For instance, have a little channel or inset along the inside of the top of the wall. You then have panels or sets of timber you can place to sit into the insets. You’ve now turned your garden bed into a long wide bench. Useful for seating guests for parties or maybe an extra place to lie down or relax. If you break up the bed area into sections, you could cover a varying amount of the bed – leaving some open to continue the vegetable garden, or for other plants like trees etc.

A way to remove or reduce the bed/s should you not want them. Perhaps have them lower so, in the event they’re not used, you can turn them into something like a sandpit or even a pond! Change the type of activity or feature.

Start small. Design one garden bed, with some additional space nearby. This space can be set up to accommodate future expansion if you find you want to have more vegetable garden bed space. That empty spot, at least initially, can be filled with temporary potted plants – a few basic varieties that provide colour and soften the space. You have your one garden bed that you will have your vegetable patch in. If you find you want more space in the future, you now have room to expand and build into that space, without ruining anything else.

This type of approach, if your activity requires it, may need you to build in any necessary equipment or access right from the beginning. So for the raised vegetable beds, if you want a particular level of drainage, you build it into the ‘empty space’ just in case you want to access it later. If you don’t really use it, no harm beyond a little bit of money. If you do find you want to use it, you already have the expensive, underground infrastructure in place, ready to use. Much easier and cheaper than ripping it up, or randomly attaching things to the work you did previously.

Design Your Garden to handle the ‘worst’ right from that start!

So this little bit of forethought – planning ahead for multiple eventualities – is how to design your garden like a professional. Create the framework to allow different options even after you’ve built something! You can choose to do something based on what you believe to be true now, but include contingencies that allow you to pivot should they change.

You won’t necessarily get it right every time, or predict every eventuality, but design your garden to be flexibile. Think about the likely thing/s that could change, and see if you can mitigate or manage them – what’s a suitable solution, when you won’t know the exact reason?

In this case, the highest probable change is around a lack of time or inclination to maintain a garden of 80 sq feet. The easiest way to remedy this is to reduce the sq ft to something manageable. It doesn’t necessarily mean I need a specific plan in place. I just need to think of a way to allow somethingto change.

I could do some of the things listed above. Start with a smaller thing that can expand. Start with specifically sized components you think should be suitable. Allow changes in materials to change the way you use a space. Or cover the space to reduce the area you work on.

So let’s go back and recap what we’ve covered.

Like choosing activities that suit you, you need to shape the activities to suit you.

Think about how much space you need for that activity for you and your family. How big is too big? How small is too small?

Consider: how much or little time you would spend doing it/looking at it? How much time you would dedicate to maintaining it?

To help you get a grasp on this, imagine the space/feature in a bad state. It’s overgrown, messy, tangled – a mess. Or, everything died, and it’s just bare and empty. If this worst case scenario came to pass, would the position you are testing it in be able to “hide” it? Is this position out in the open? Clearly visible?

If they were to become overgrown or messy, which positions would ‘hide’ it more?

Then, let’s think about some ways to mitigate this worst case. Design some ways to add/subtract materials. Change the program a little. Or a lot. Or half way. Allow space to expand easily if you’re not sure how much space you’ll need. Provide a framework for contingencies to occur.

And this is kind of it. We’re getting down to the crux of design.

Where you build in infrastructure for changes you may not be able to foresee, but could lead to the same outcome (like reducing the amount of space I’d need to care for a vegetable garden).

That’s really it for this post. Remember to design your garden for YOU! To imagine how you’d use a space. Imagine possible scenarios that could occur. Build in plans to accommodate those changes.

All of this is part of my landscape design process. Read more here, or check out my guide, The Garden Design Process.